Home Page

Free Newsletter

What's New

eCatalog

Audio Clips

Reviews

To Order

Payment Options

Shipping Info

Search

Profiles

About eCaroh

Things Caribbean

Profiles of Caribbean Artistry

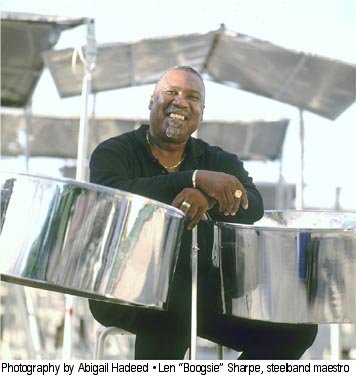

PAN PASSION

Composer, arranger and steelband virtuoso, Len "Boogsie" Sharpe is a legend

in Trinidad, the island that invented the instrument. Pat Bishop, artist,

pan and choral conductor and herself an acclaimed steelband arranger, discusses

the brilliance of Sharpe’s work over the last 30 years

Composer, arranger and steelband virtuoso, Len "Boogsie" Sharpe is a legend

in Trinidad, the island that invented the instrument. Pat Bishop, artist,

pan and choral conductor and herself an acclaimed steelband arranger, discusses

the brilliance of Sharpe’s work over the last 30 years

Some time in the period between the two World Wars, Trinidadians of the urban

underclass transformed drums, which had been used to contain oil, into musical

instruments. Lennox Sharpe, also known as "Boogsie", plays this steel drum or

steel pan better than most of the instruments’ other practitioners. He also

invents music for it for himself as a solo performer, as well as for bands. In

the manner of the jazz musician, he improvises with virtuosic skill upon popular

melodies but he also produces original music, even to specific themes. This

music is hardly ever commonplace and could hold its own in the wider world of

musical composition, if Trinidad ever got around to taking its music seriously.

But Trinidad is geographically small and remote and is seen as utterly

unimportant in world affairs. As a consequence, Boogsie endures the same fate as

the island which is his home, and, ironically, his inspiration.

Some time in the period between the two World Wars, Trinidadians of the urban

underclass transformed drums, which had been used to contain oil, into musical

instruments. Lennox Sharpe, also known as "Boogsie", plays this steel drum or

steel pan better than most of the instruments’ other practitioners. He also

invents music for it for himself as a solo performer, as well as for bands. In

the manner of the jazz musician, he improvises with virtuosic skill upon popular

melodies but he also produces original music, even to specific themes. This

music is hardly ever commonplace and could hold its own in the wider world of

musical composition, if Trinidad ever got around to taking its music seriously.

But Trinidad is geographically small and remote and is seen as utterly

unimportant in world affairs. As a consequence, Boogsie endures the same fate as

the island which is his home, and, ironically, his inspiration.

It is said that Boogsie learned to play his first pan at the age of four, and while he was still a little boy he became an established member of the now-defunct Crossfire and Symphonettes steelbands. As a youngster, he also played with Invaders. Then he went to Starlift, the steelband for which Ray Holman was taking the revolutionary step of composing music specifically for the instrument.

Boogsie was quick to continue what Holman had started, and by 1972 he had established Phase II Pan Groove, the band which he continues to lead. Through that association he has been enriching the music of Carnival with his own remarkable sense of sound, of harmony and rhythm and of the musical possibilities of the steel drum instrument in ensemble.

Carnival has always needed music. It is the driving force behind Carnival energy; it is the "motor" which keeps the Carnival processions moving. Steelband had its birth in the Carnival requirement for musical accompaniment. For this reason, the music is described as needing "a high tempo, volume and energy level". Panorama is the main pan competition and its music is seldom soft, slow or contemplative. It is difficult to coax musical originality in the face of these limitations. But Boogsie can. There is a piece by the American minimalist composer, John Adams, which he calls Short Ride In A Fast Machine, and that title very aptly describes Boogsie’s Carnival pan music.

Boogsie’s contributions to Panorama range from Pan Rebels through to

’79 is Mine. These are the years of his growth, leading to the seminal

I Music of 1984. Today his Panorama music continues to be the most

innovative. According to Knolly Moses, a New York-based Trinidadian writing in

the Key Caribbean Carnival magazine of 1984, I Music began with a

ripe and textured introduction and a phrasing of the low pans that must be the

sweetest line ever heard on a Panorama night. The band then laid out a clear-cut

melody through the mandatory number of bars to establish the tune in the

listener’s mind. Then Boogsie went to work. The tenors swiped at notes in what

jazz musicians would call riffs. He twisted and reshaped the melody sometimes

beyond recognition. Frills and flourishes flew in all directions.

Boogsie’s contributions to Panorama range from Pan Rebels through to

’79 is Mine. These are the years of his growth, leading to the seminal

I Music of 1984. Today his Panorama music continues to be the most

innovative. According to Knolly Moses, a New York-based Trinidadian writing in

the Key Caribbean Carnival magazine of 1984, I Music began with a

ripe and textured introduction and a phrasing of the low pans that must be the

sweetest line ever heard on a Panorama night. The band then laid out a clear-cut

melody through the mandatory number of bars to establish the tune in the

listener’s mind. Then Boogsie went to work. The tenors swiped at notes in what

jazz musicians would call riffs. He twisted and reshaped the melody sometimes

beyond recognition. Frills and flourishes flew in all directions.

"Sometimes the tune would appear out of a floating line only to disappear into a skirmish of chords. He phrased lines so obliquely they sounded like jazz licks from some jam session. Most of all, he jammed in classic fashion though at a slower tempo . . . At one point, the pans whispered a line so softly it swapped a silent secret between the arranger and his audience. Boogsie drew pulse and breath from his major musical influences, Stevie Wonder and Herbie Hancock. He fused funk, rock, jazz and soca."

During the 1960s and 70s, young classically trained American composers increasingly rebelled against the conventional futurist opinion that serialism of a kind was the only valid language for truthful and original modernist expression. To them, the European avant garde was irrelevant, and they began to draw inspiration from the music of their everyday milieu, notably contemporary rock. Boogsie Sharpe had come from no such background. Musical education was not widespread in his youth and, in any event, who in Trinidad had ever heard of serial music? Then or now? But the outcome of these divergent processes was closer than one might imagine. By the time Sharpe produced Musical Wine for Carnival 1985, he was creating music bi-tonally — within the same bars, one set of instruments was playing in one key and a second set, simultaneously, in another.

But nobody had taught Boogsie anything. Instead, he was listening to the noises of the street and participating in jazz sessions on his steel pan with other musicians. By 1985, Andy Narell, the American jazz-pan musician, described Phase II, Boogsie’s band, as being "at the cutting edge of steel band music." Narell had come to Trinidad to play in the Carnival Panorama and joined Phase II for the occasion, putting his own pan sticks at the service of Sharpe’s reputation.

It may, therefore, be useful to review the steelband environment in order to give some sort of framework through which Boogsie’s work may be better understood and evaluated. The people who transformed the steel drum into a musical instrument were the urban underclasses of the various suburbs of Port of Spain. Most steel band histories like to trace an unbroken pattern of development in respect of the musical capability of the drum as a musical instrument. They take account of its origins as a drum — both as a container and as a percussion instrument. Indeed, it is ironical that in the steel band lexicon, a drum is also a drum! Because the steel drum’s origins lie in the bamboo drum (the patois bamboo tambour) or the skin drum. The decisive change occurs when metal containers with drumheads on which the tuning can be fixed are substituted.

The steelband story continues to tell that, first of all, the drumhead is raised. Later it is sunk. Nobody quite agrees about who tuned the first note. Popular legend attributes the discovery to Winston Simon, also known as "Spree". It really doesn’t matter who did it, because in the fierce rivalry which obtained among the districts, today’s invention became everybody’s possession. In the manner of street gangs everywhere, the groups were young and rebellious, giving themselves names of war and danger. Such groups included Invaders, Desperadoes, Tokyo, Casablanca; and, as the movement spread throughout Trinidad and Tobago, we find the "Free French" in San Fernando. Intra-class rivalry was to involve these gangs in pitched battles, especially at Carnival, when the steel drum was both shield and shibboleth.

The rise of nationalist politics in the 1950s was to change all that.

Commercial sponsorship institutionalised and tamed steelband gang rivalry by

giving money to bands for good behaviour and also for good music. This gave rise

to the Panorama Competition and created the artistic milieu in which Boogsie

Sharpe principally works.

The rise of nationalist politics in the 1950s was to change all that.

Commercial sponsorship institutionalised and tamed steelband gang rivalry by

giving money to bands for good behaviour and also for good music. This gave rise

to the Panorama Competition and created the artistic milieu in which Boogsie

Sharpe principally works.

It must not, however, be forgotten that the music which is being discussed at the moment is Carnival music. Essentially populist, the Panorama tune is a theme and variation work of 10 minutes’ duration in which the theme is derived from a calypso of that particular season. Supporters of the bands are often fanatically partisan, not perhaps to the degree of soccer hooligans, but the analogy will stand.

What Ray Holman did in 1973 was to give Starlift, one of the youngest bands on the scene, a compostion of his own and not a calypso. In those days, to "do" one’s "own tune" was to strike terror into the hearts of pan players. The simple logic was that "the people" wouldn’t know it, wouldn’t respond positively and the band would lose the Panorama. It was also felt that there was a special relationship between the calypsonian and the steelband which the intrusion of the specially composed theme would upset.

Despite Boogsie Sharpe’s own personal respect for calypso and its singers, his band, Phase II, has almost always played an original Sharpe composition at Panorama. On the other hand, the old calypso tradition has held, as a consequence of which, Boogsie belongs to a small and not very influential group of pan player/arrangers who pursue the path of experiment and innovation.

It may be useful now to identify the current elements which comprise the steelband movement. They are, first of all, the old community-based organisations which produced the first panmen. These organisations continue to constitute the main foundation of the pan movement.

There are also the new congregations of youngsters who are essentially

school-based. They rehearse in the yards of the community bands and are

numerically strong, but they have not yet achieved the steelband political power

commensurate with their numbers.

There are also the new congregations of youngsters who are essentially

school-based. They rehearse in the yards of the community bands and are

numerically strong, but they have not yet achieved the steelband political power

commensurate with their numbers.

Boogsie belongs to the third group, the handful of individual panmen of talent and skill who have been forced to seek musical careers abroad (since there is little opportunity for such activity on a year-round basis at home).

We therefore find Boogsie abroad as much as he is at home, seeking paying gigs wherever he can find them, for all that Trinidad and Tobago is the birthplace of steelband music. It is everywhere at Carnival time but interest in it diminishes at the level of both player and listener at other times of the year.

But from time to time there are festivals which call for a wider range of music. Traditionally, these festivals showcase classical music transcribed for steelband, and some of these performances have been splendid by any standards. Boogsie has chosen a different route, and it is in these non-Carnival pieces that his range as a composer may be best evaluated.

This essay now becomes more personal because it is in this regard that my closest contact with Boogsie Sharpe has been occurring.

I get a telephone call from pannist Junior Regrello. He plays a fragment of pan music over the telephone and asks me to give it a name. Well, of course, I cannot do any such thing. Instead, I go to the panyard with Boogsie and we discuss what the music sounds like. You must remember that I am talking to a composer who can neither read nor write music but whose sense of musical adventure is highly developed.

To me, those opening bars sounded like shuffling feet. The music sounded like the feet of douens dancing. (In the folklore of Trinidad, the douen is the spirit of a child who dies before it has been baptised. As a consequence, it is doomed to wander with its head facing one direction and its feet pointing the opposite way.) This little shuffle of Boogsie’s seemed to be a minimalist kind of phrase repeated over and over, breaking into six-eight time for a bar or two before being repeated.

Sitting with Boogsie and the players of the Skiffle Bunch steelband, we concocted an imaginary scenario in which the douens give a party to which they invite a whole host of other characters from folklore. The interesting thing about this music is the fact that Boogsie invented it upon a set of traditional pans with a very limited range of notes. Each intervention in the music represented the arrival at the dance of a new character. The end of the piece recapitulates the opening ideas and is finished by crashing sounds of sonic enthusiasm.

The piece came first in its category in the Steelband Music Festival. Not surprisingly, the choreographer Patricia Roe recognised its balletic qualities and created a piece for The Caribbean School of Dance, in which the band itself was choreographed into the ballet. No photographs of this event have survived, but later on Boogsie developed the piece for Phase II, in whose repertoire it survived for a longer time.

The same process of music and story line in combination persisted through The Saga of the San Fernando Hill and The Three Seasons. Later on, he was to do Faces for the St Augustine Senior Comprehensive School Band. Most recently, he set a Rain Forest scenario to music for the Skiffle Bunch, now reconfigured into a conventional steelband with the full range of notes. That piece helped Skiffle Bunch win the first World Steelband Festival in 2000; in it, Boogsie improvises a few bars of such virtuosic authority that no one could deny his genius as a performer.

I have mentioned minimalism. I also need to say that Sharpe’s understanding of counterpoint is highly developed. His method of working is instructive. He goes to an instrument — he plays them all — and starts to play whatever is in his head. Or perhaps he calls the notes and note values to a player. It is only after he has gone through the full range of instruments that we hear what the piece really is. Each section is given something to play which is often quite complete in itself. But the magic is made in the combination.

In recent years, as he has become more familiar with the piano and because he plays increasingly alongside musicians on other instruments, Boogsie’s sense of music as melody and chord has been strengthened, at the expense of the wild counterpoint of his earlier years. But what has grown is his minimalism in which small phrases are repeated again and again until they achieve a mantra-like quality.

For all that Boogsie is a popular personality, his music remains a mystery, even to his fans and to those who play it. But there is no question about his virtuosity as a soloist. His improvisational skills are as good as any and better than many.

A few months ago, Boogsie played for a gathering of recovering drug addicts. I had gone to speak; he was there to play. The material which he offered was simple enough — a medley of Christmas melodies. Ah, but the magic! There was no accompanying band, not even a piano. But with two pans and two sticks, he made all kinds of harmonic inventions and interventions, laying out metallic music like a tapestry of sound, the like of which, it seemed, I had never heard before.

One of the most interesting of Carnival experiences is to go to a panyard to watch the arrangers at work during the preparation of a steelband for Panorama. Of these, Boogsie Sharpe at Phase II may be the most interesting. It is not entertainment. Many of the fans want to hear the whole piece quickly so that they can go on to the next band. But it is worth taking the time to watch the growth of a Boogsie creation.

My own experience occurred during the Carnival of 1986. The piece was Pan Rising. I heard it and watched it unwind from the mind of the musician, night after night, seamlessly, each section following, with musical inevitability, one on the other. I would go home night after night to work on a painting — 12 feet long — which tried to show what I was hearing. The painting didn’t turn out to be much. But the music . . . that, as we say, was something else! It remains with me as both hope and achievement. Hope that one day the pan will really rise and take its place among the existing family of musical instruments. Achievement in that Pan Rising may, more than most pan pieces, indicate that pan has already risen. But as I said before, this is Trinidad, which is small, geographically remote and unimportant in world affairs. As a consequence, Boogsie Sharpe endures the same fate as the island which is his home and, ironically, his inspiration.

VINTAGE BOOGSIE

An enthusiastic Boogsie-watcher described a performance of his in 1984 in the following words:

With arrangements of high tenors, double-tenors and guitarpans, Boogsie led, with Valentino’s Life Is A Stage, playing the different pans in a jazzy interpretation and using the pitch of each pan to highly dramatic effect. Then, he switched to Relator’s Gavaskar. The finely tuned pans answered his every call of musical expression — forte to pianissimo.

But it was when Boogsie, member/arranger of Phase II Pan Groove, switched from Terror’s Pan Talent to Kitchener’s Sweet Pan that the capacity audience roared its acclaim of the versatility.

More was yet to come. Next, Boogsie was playing the high tenor pan held upside down by an assistant. In other words, he was playing the tune on the bottom side of the pan. He then ventured into extemporaneous musical expressions that brought the crowd to its feet.

For the finale, he sobered the crowd with an exhilarating performance of his own 1984 composition, I Music — this time playing the pans from the front side of the instruments, rather than from behind the pans — the customary position. By the close of his half-hour performance, this superstar of second generation panmen was as fresh as when he had started.

This article is included with the permission

of the publisher

Caribbean Beat, September-October 2002 issue

© 2002 Media & Editorial Projects Ltd